Panoramic view of the Waterbuurt and Schoonschip floating houses in Amsterdam (source: Theguardian).

In principle, the Amsterdam floating house is a fixed house placed on a floating structure, which is different from a traditional boathouse. Each house is placed on a hollow, watertight box-shaped reinforced concrete block (caisson). This block sinks about half a floor below the water level, creating thrust and lowering the center of gravity, helping the house to be stable against waves and winds. [3][4] The upper is a light steel or wood frame, covered with panel walls and large glass arrays to reduce loads, taking advantage of natural lighting and views of the water. [3]

A multi-storey floating house with a hollow concrete foundation and a wooden and glass body (Schoonschip, Amsterdam)

The house is anchored to steel or concrete piles inserted deep into the bottom of the lake. Through the sliding ring mechanism, the whole building can go up and down according to the water level but not horizontally. Electrical, water, drainage and telecommunication cables run along piers or anchor piles, using flexible joints to withstand the relative displacement between the house and the shore. [1][3] Thanks to the prefabricated design in the workshop and then pulled to the installation location, the quality of the work is well controlled, the construction time is shortened and the cost is close to the house built on land in the same area. [3][4]

The floating structure combined with the submerged concrete block creates a natural "heat buffer": the surrounding water absorbs and releases heat more slowly than air, helping to reduce the amplitude of indoor temperature fluctuations and the need for air conditioning. [4] This is especially evident in low-lying spaces, which are partly below the surface of the water.

The Waterbuurt (Water District) is located in the new IJburg district east of Amsterdam, which is one of the first large-scale floating residential areas in Europe. [3][4] The first phase of the project consisted of about 55–75 floating houses, along with a number of houses on the shore, forming a waterfront with a density comparable to traditional downtowns. [3] Each unit is about 120 m² wide, 2–3 storeys high, with a common spatial organization: the lowest floor (semi-negative under the water) is the bedroom; The upper floors are living spaces, combined with balconies or terraces overlooking the lake. [3][4]

Waterbuurt floating residential area in IJburg, clusters of floating houses are arranged along the pier (source: Monteflore)

The houses were designed by architect Marlies Rohmer in a simple cubic language, emphasizing practicality. The façade uses wood, light-colored cladding and many glass arrays, creating a "modern neighborhood on the water" but still in harmony with the landscape. [3] The whole area is connected by a floating pier system, which serves as an internal road and outdoor community space.

Socially, Waterbuurt's residents are mostly middle-class families, not necessarily associated with the maritime profession. They choose to live on the water because of the quiet environment, close to nature but still about 15 minutes from the city center by public transportation. [1][4] Waterbuurt shows that floating houses are not only a technical solution to prevent flooding, but can become an attractive type of housing in terms of quality of life.

If Waterbuurt is a "proof of concept", then Schoonschip is a step forward in sustainability and circular economy. The project was initiated by a group of residents around 2010, with the goal of building "the most sustainable floating neighborhood in Europe". [5] Completed in 2021, Schoonschip consists of 46 houses on 30 floating platforms, arranged along the Johan van Hasselt Canal in northern Amsterdam. [5][6]

In terms of architecture, each house is designed by a different group of architects, creating a diversity of shapes and materials but agreeing on the criteria: using low-emission materials, integrating a green roof and optimizing natural lighting. [5] The floating houses are connected to each other and to the shore by a central jetty (smart jetty), where technical infrastructure and public space organization are concentrated

In terms of environmental engineering, Schoonschip operates as a floating microgrid. The whole area has installed about 500 solar panels, combined with water heat pumps and energy storage systems, allowing households to share electricity through a smart grid, only one point is needed to connect to the national grid. [5][6] Wastewater is separated into gray water and black water; Black water is bioprocessed to recover energy and nutrients. [6] Green roofs and floating structures planted with trees contribute to reducing the heat island effect and increasing biodiversity in the heart of the city.[ 6]

Socially, Schoonschip is a self-governing community where residents organize into groups in charge of energy, water, shared transportation, and community activities. [6][7] This model shows that floating houses can be the nucleus for green and cohesive lifestyles, rather than just a single building solution.

From a climate adaptation perspective, floating houses allow residential areas to rise with the water level instead of having to be relocated when flooding occurs. This is especially important in low-lying plains, where rising sea levels threaten livelihoods and land banks. [1][2] At the same time, the development of water housing helps to expand urban space without having to encroach deeply on agricultural land or natural spaces. [2][3]

For Vietnam, where the Mekong Delta, the Central region and coastal cities are under great pressure from flooding and high tides, the Amsterdam experience suggests a new approach to the "living with flood" mindset. In addition to traditional stilt houses and raft houses, it is possible to study and pilot a cluster of floating community houses with concrete floating structures, anchoring piles and infrastructure connections similar to Waterbuurt, combining renewable energy solutions, water and waste management in the direction of Schoonschip.

However, the application should be accompanied by careful study of hydrological conditions, the load capacity of the canal system, the cost-financial story and the legal framework (construction regulations, registration of floating house ownership). Cooperation with experienced units in the Netherlands, in parallel with the localization of materials and technology, will be the key for the floating house model to become feasible in Vietnam.

[1] Rubin, S. (2021). Embracing a Wetter Future, the Dutch Turn to Floating Homes. Yale Environment 360. Available: https://e360.yale.edu/features/the-dutch-flock-to-floating-homes-embracing-a-wetter-future

[2] Henley, J. (2025). Living with the water: the Netherlands' floating futures. The Guardian. Available : https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/nov/10/living-with-the-water-the-netherlands-floating-futures-photo-essay

[3] Architectenbureau Marlies Rohmer (2010). Floating Houses in IJburg. ArchDaily. Available: https://www.archdaily.com/120238/floating-houses-in-ijburg-architectenbureau-marlies-rohmer

[4] Sanburn, J. (2014). This Floating City May Be the Future of Coastal Living. TIME. Available: https://time.com/2926425/the-floating-homes/

[5] Space&Matter (2021). Schoonschip – a sustainable floating community. Space&Matter. Available: https://www.spaceandmatter.nl/project/schoonschip

[6] Metabolic (2019). Schoonschip – A Circular Neighborhood on Water. Metabolic. Available: https://www.metabolic.nl/projects/schoonschip/

[7] CityChangers (2023). Schoonschip: A Floating Neighbourhood. Available: https://citychangers.org/schoonschip-floating-neighbourhood/

The News 20/11/2025

Kampung Admiralty - the project that won the "Building of the Year 2018" award at the World Architecture Festival - is a clear demonstration of smart tropical green architecture. With a three-storey "club sandwich" design, a natural ventilation system that saves 13% of cooling energy, and a 125% greening rate, this project opens up many valuable lessons for Vietnamese urban projects in the context of climate change.

The News 10/11/2025

In the midst of the hustle and bustle of urban life, many Vietnamese families are looking for a different living space – where they can enjoy modernity without being far from nature. Tropical Modern villa architecture is the perfect answer to this need. Not only an aesthetic trend, this is also a smart design philosophy, harmoniously combining technology, local materials and Vietnam's typical tropical climate.

The News 25/10/2025

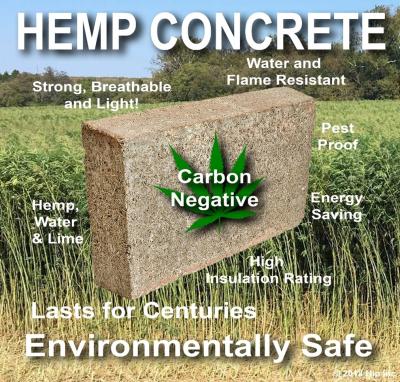

Hemp-lime (hempcrete) is a non-load-bearing covering material consisting of a hemp wood core (hemp shiv/hurd) combined with a lime-based adhesive, outstanding for its insulation – moisture conditioning – indoor environmental durability; in particular, IRC 2024 – Appendix BL has established a normative line applicable to low-rise housing, strengthening the technical-legal feasibility of this biomaterial.

The News 11/10/2025

Amid rapid urbanization and global climate change, architecture is not only construction but also the art of harmonizing people, the environment, and technology. The Bahrain World Trade Center (BWTC)—the iconic twin towers in Manama, Bahrain—is a vivid testament to this fusion. Completed in 2008, BWTC is not only the tallest building in Bahrain (240 meters) but also the first building in the world to integrate wind turbines into its primary structure, supplying renewable energy to itself [1]. This article explores the BWTC’s structural system and design principles, examining how it overcomes the challenges of a desert environment to become a convincing sustainable model for future cities. Through an academic lens, we will see that BWTC is not merely a building but a declaration of architectural creativity.

The News 04/10/2025

As buildings move toward net zero architecture and glare free daylighting, traditional glass façades reveal limitations: high thermal conductivity (~0.9–1.0 W/m·K), susceptibility to glare, and shattering on impact. In this context, transparent wood (TW) is emerging as a multifunctional bio based material: it offers high light transmission yet strong diffusion (high haze) to prevent glare, lower thermal conductivity than glass, and tough, non shattering failure. Recent reviews in Energy & Buildings (2025) and Cellulose (2023) regard TW as a candidate for next generation windows and skylights in energy efficient buildings. [1]

The News 27/09/2025

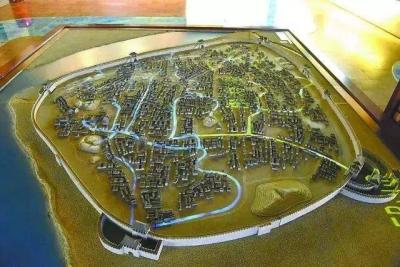

Urban flooding is one of the greatest challenges of the modern era, when sudden and unpredictable rainstorms can paralyze entire cities. Few would imagine that over a thousand years ago, people had already discovered a sustainable solution: the Fushougou drainage system in the ancient city of Ganzhou, Jiangxi. Built during the Northern Song dynasty, this project remains effective to this day, protecting the city from floods—even during historic deluges. The story of Fushougou is not only a testament to ancient engineering but also a valuable reference for today’s cities seeking answers to water and flooding problems.