New York City mandates private stormwater collection in most new developments. That almost always means underground reservoirs.

Brooklyn’s Bergen project is an exception.

The residential development currently under construction features two waterfalls and a reflection pond that bring the process of controlling runoff to the surface, exposing bare the effects of climate change. But rather than serve as an ominous reminder of the consequences of intensifying weather, the designers intend for the project’s landscape to demonstrate a way to adapt.

“Why is the response to dealing with this new reality something that always lives in the basement or underground?” asks Jordan Rogove, partner and cofounder of DXA Studio, who did the master planning on the project. “It’s just a new reality and we should embrace it and, more importantly, provide people an opportunity to experience it in a really beautiful way.”

The condominium project, designed by Frida Escobedo, presented Rogove and landscape designer Patrick Cullina a considerable engineering challenge: 45,000 square feet of surface area collecting rainwater in Brooklyn, “which arguably has the most outdated sort of stormwater conveyance system in the city,” Rogove says.

However, the immensity of the site allowed for flexibility. By strategically massing the building, the team was able to create lush outdoor environments that serve double duty as water management systems and an amenity.

“In New York, we have all of this impermeable space, and all that water runs off without being used to sustain a living landscape,” says Cullina, a key figure in the Brooklyn Botanical Garden and New York City’s High Line urban park. “My thought was to develop and expand the possibility for permeability.”

Rainstorms turn the landscape into a dynamic environment complete with plants that aid permeability. Water cascades down terraces and through channels into a reservoir that releases water into the public system once there’s enough capacity.

“We’re stacking benefits vertically. For the same nickel, you get stormwater management, air quality improvement, wildlife habitat, and aesthetic pleasure,” Cullina says.

Bergen’s design incorporates all four classical elements: earth, air, fire, and water. Earth is represented through the robust masonry of the building and the lush plantings. Air is celebrated with kinetic sculptures and the natural movement of plants swaying in the breeze. Water, as mentioned, is ever-present through a static mirror pond, runnels, and waterfalls, while fire is acknowledged with outdoor fire pits, adding warmth and gathering spaces for residents.

The gardens change with the seasons, creating a lively, evolving experience for residents.

“The idea that you can be in a park-like setting and still be in your home is extraordinarily unique for the city,” Cullina says.

Bergen not only addresses the practical challenges of stormwater management and urban density but also offers a vision for how cities can adapt to a changing climate while enhancing the quality of urban life.

“Water is a beautiful thing,” Rogove says. “Don’t treat it like an enemy—embrace it.”

The News 25/12/2025

Walking by Ba Son at night and seeing the sky like "turning on the screen"? It is highly likely that you have just met Saigon Marina International Financial Centre (Saigon Marina IFC) – a 55-storey tower at No. 2 Ton Duc Thang (District 1). The façade LED system makes the building look like a giant "LED Matrix": standing far away, you feel like the whole tower is broadcasting content, constantly changing scenes according to the script.

The News 14/12/2025

Architectural Digest gợi ý Cloud Dancer phù hợp với plush fabrics và những hình khối “mềm”, tránh cảm giác cứng/rigid; họ liên hệ nó với cảm giác “weightless fullness” (nhẹ nhưng đầy) [3]. Đây là cơ hội cho các dòng vải bọc, rèm, thảm, bedding: màu trắng ngà làm nổi sợi dệt và tạo cảm giác chạm “ấm”.Pantone has announced the PANTONE 11-4201 Cloud Dancer as the Color of the Year 2026: a "buoyant" and balanced white, described as a whisper of peace in the midst of a noisy world. This is also the first time Pantone has chosen a white color since the "Color of the Year" program began in 1999. Pantone calls Cloud Dancer a "lofty/billowy" white tone that has a relaxing feel, giving the mind more space to create and innovate [1].

The News 04/12/2025

The Netherlands is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change, with about a third of its area lying below sea level and the rest regularly at risk of flooding. As sea levels are forecast to continue to rise and extreme rains increase, the government is not only strengthening dikes and tidal culverts, but also testing new adaptation models. Floating housing in Amsterdam – typically the Waterbuurt and Schoonschip districts – is seen as "urban laboratories" for a new way of living: not only fighting floods, but actively living with water. In parallel with climate pressures, Amsterdam faces a shortage of housing and scarce land funds. The expansion of the city to the water helps solve two problems at the same time: increasing the supply of housing without encroaching on more land, and at the same time testing an urban model that is able to adapt to flooding and sea level rise.

The News 20/11/2025

Kampung Admiralty - the project that won the "Building of the Year 2018" award at the World Architecture Festival - is a clear demonstration of smart tropical green architecture. With a three-storey "club sandwich" design, a natural ventilation system that saves 13% of cooling energy, and a 125% greening rate, this project opens up many valuable lessons for Vietnamese urban projects in the context of climate change.

The News 10/11/2025

In the midst of the hustle and bustle of urban life, many Vietnamese families are looking for a different living space – where they can enjoy modernity without being far from nature. Tropical Modern villa architecture is the perfect answer to this need. Not only an aesthetic trend, this is also a smart design philosophy, harmoniously combining technology, local materials and Vietnam's typical tropical climate.

The News 25/10/2025

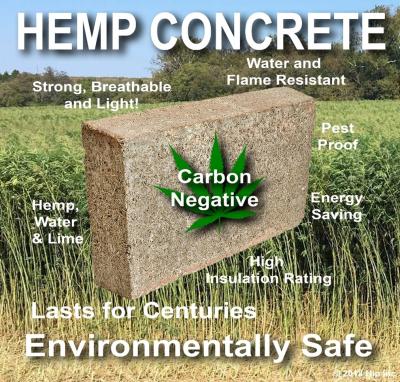

Hemp-lime (hempcrete) is a non-load-bearing covering material consisting of a hemp wood core (hemp shiv/hurd) combined with a lime-based adhesive, outstanding for its insulation – moisture conditioning – indoor environmental durability; in particular, IRC 2024 – Appendix BL has established a normative line applicable to low-rise housing, strengthening the technical-legal feasibility of this biomaterial.